It’s 4:55pm Central Time on a Tuesday at Bumble headquarters in Austin, Texas. Whitney Wolfe Herd, the 28-year-old founder and CEO of the woman-led dating app is showing me around the nearly four-year-old startup’s office before we sit down to talk.

Our first stop is the standard startup watering hole, with a few twists. The fridges are stocked with Topo Chico instead of La Croix and the built-in taps are purely for decoration. Maybe one day they’ll be filled with Kombucha or iced coffee, a team member tells me. But no mention of beer. We’re not in Silicon Valley anymore.

As Wolfe Herd pours two glasses of white wine and plops in a few ice cubes, she briefly pauses to ask if I’m okay with the drink selection. Her question quickly caused my mind to wander back to my 21st birthday when a waiter told me men aren’t supposed to drink white wine with ice cubes.

There was perhaps no better way to begin my time with Wolfe Herd than a reminder that no matter how many hundreds of millions of woman-initiated matches have been made on Bumble, the company still exists in a world so ingrained with gender stereotypes that we couldn’t get through pouring a drink before the first one reared its head.

Luckily for me and my unsophisticated palate, I’d soon learn that Whitney Wolfe Herd doesn’t particularly care what people think that she or Bumble are supposed to do, let alone what we should be drinking.

‘I’m not building a dating app’

Bumble isn’t Wolfe Herd’s first exposure to the world of digital dating and connections. She moved to Los Angeles in 2012 and became an early co-founder of Tinder, but eventually left the company amid allegations of sexual harassment and discrimination against another one of the company’s co-founders. The lawsuit was settled, and while the past is the past, the history does help set the stage for the idea that would eventually turn into Bumble.

“I was just poof, gone, ceased to exist. It was like leaving behind an abandoned life, fleeing from the storm or whatever it was,” explained Wolfe Herd when talking about leaving Los Angeles after her time at Tinder. “I was experiencing all this, and then the Twitterverse and the Instagram world and the online sphere started attacking me. And I had never really understood online bullying. I didn’t even know what that meant or what it felt like. It made me really depressed.”

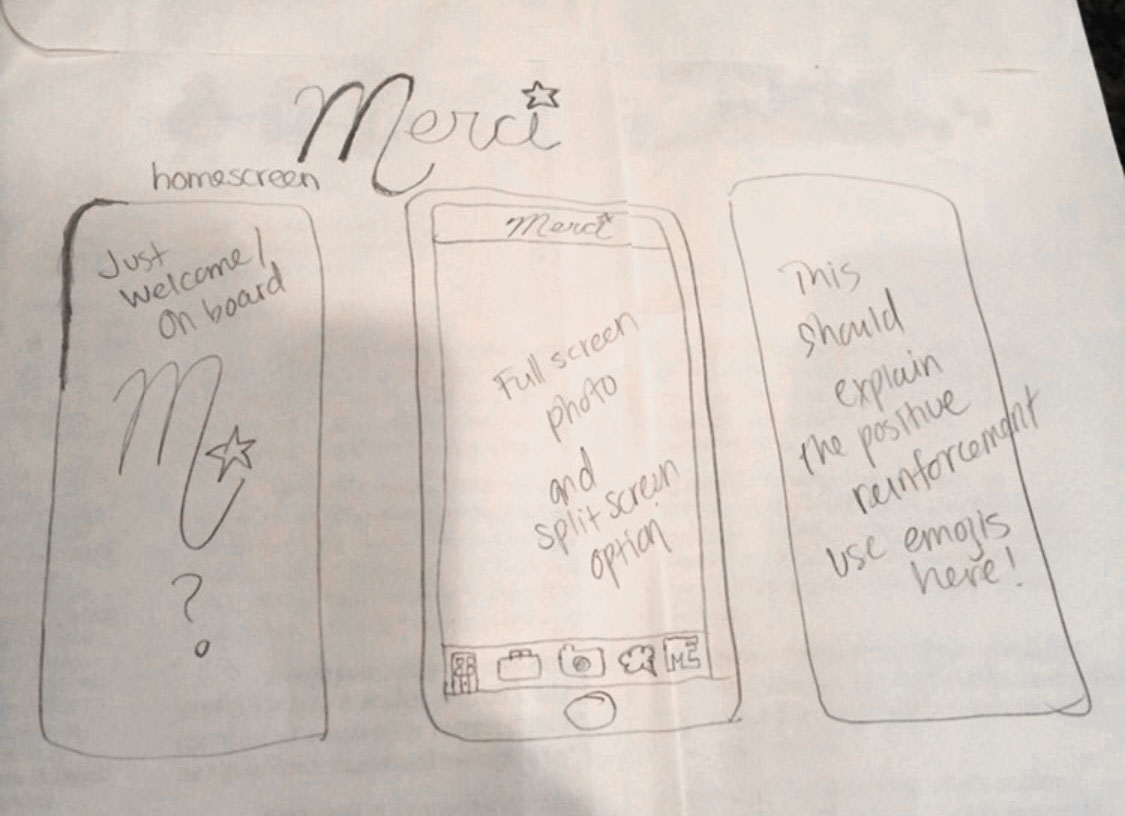

As successful entrepreneurs are known to do, Wolfe Herd soon began figuring out a way to leverage these closely held personal experiences into a new product. Her solution was Merci, a female-only social network “rooted in compliments and kindness and good behavior.”

Original mockup of Bumble, then known as Merci

While she was building out the idea, Andrey Andreev, founder and CEO of Badoo, the largest dating platform in the world, contacted her. Little did Wolfe Herd know, but Andreev saw her departure from Tinder as an opportunity, inviting her to meet the Badoo team in London where it had been based for more than 10 years. After some reluctance on Wolfe Herd’s part, she decided to go for it. After all, she was looking for feedback on her Merci idea, and worst-case she’d at least leave with a better idea of what she wanted to build next.

But Andreev had other plans. During their first meeting he frankly asked Wolfe Herd to become the chief marketing officer of Badoo.

She didn’t even consider the offer. First, it would have required her to move to London and, more importantly she was adamant about never working in the dating world again. With the CMO offer in the meeting’s rearview mirror, Wolfe Herd shifted the conversation to Merci, and gave Andreev a deep dive into her idea for a woman-only social network grounded in compliments and positive feedback.

“I love it,” Andreev said. “We’re going to name the dating app Merci.”

She was aghast, even in her retelling of the story.

“The what? What are you talking about? Did you hear what I said? I’m not building a dating app. Merci is the name of my female-only social network.”

Andreev clarified: “I love your vision for a female-first platform, but you need to do this in dating.”

He essentially offered her the funding she needed to get the app off the ground, and, perhaps more importantly, full access to Badoo’s technical team to build and ship it. Plus, full creative control and decision-making ability regarding the direction of the new company.

From L-R: Whitney Wolfe Herd, Andrey Andreev and Sarah Jones Simmer, Bumble’s COO

But Wolfe Herd had no interest in building such an app, and Andreev had no interest in getting involved with a new social network. So she headed home, all the more determined to make Merci the next big thing. But the offer from Andreev was still lingering in the back of her mind.

“My husband, boyfriend, whatever you want to call him — Michael, we’ll just call him Michael,” Wolfe Herd told me. “Michael was like, ‘Whit, this opportunity doesn’t strike twice. You’re going to try and raise money right now? You’re literally a scorned seductress, according to the VC community right now. Good luck to you. I know you don’t have the backbone right now,’ because I had been so depleted and I was so low on myself.”

With the encouragement of her then-boyfriend (now husband) Michael Herd, she decided that Andreev’s offer was too good to pass up, and headed back to London, where she essentially made a handshake deal with him to build this new woman-first dating app.

Bumble was born

The company would exist as a new entity with 20 percent ownership belonging to Wolfe Herd, 79 percent to Badoo and 1 percent divided between Christopher Gulczynski and Sarah Mick, two early consultants who went on to join full-time after the company was up and running. Briefly named Moxie, the group settled on Bumble after a trademark search turned up conflicts.

Bumble would be run independently from Austin, Texas, with the ability to tap into Andreev and Badoo’s years of experience in the dating industry when needed. It certainly wasn’t a typical arrangement, especially in the world of tech startups where, in order to build a successful company, you’re supposed to rally a group of two to three co-founders, raise a seed round, then a Series A and so on.

But now, four years and 30 million users later, Bumble’s cap table looks exactly the same as it did the day the company was founded. Wolfe Herd’s 20 percent undiluted founder’s stake is evidence that an atypical path was right for Bumble.

A startup office with no engineers

It quickly becomes apparent to me as a technology writer walking through Bumble’s Austin headquarters that this isn’t your typical startup office. It looks and feels much more like a living room than any sort of standard tech office environment.

For a small space that is now overflowing with more than 50 employees, there are only about 25 desks, and most of those remained empty during my two-day visit. Everyone seems to prefer rotating through conference rooms, counters, coffee tables, floors and the largest couch I’ve ever seen, which sits in a semicircle ready to comfortably fit upwards of 30 people, if needed.

“I believe in taking people away from their desks and making them feel collaborative and inspire one another instead of being siloed,” she explained.

While the setup may not work for some companies, it certainly does for Bumble. But that doesn’t mean everyone agrees. Wolfe Herd explained that they had to rotate through multiple designers before settling on one that aligned with her vision.

“So many people wanted to make it hyper functional and minimalistic and stark…almost cold,” she told me. “I didn’t want it to feel that way. I wanted it to feel welcoming and warm and do it differently.”

The design isn’t the only thing that stands out when walking through Bumble’s office. It also doesn’t have a single engineer.

Just like Andreev promised Wolfe Herd when they first decided to build Bumble, all engineering is still handled in Badoo’s London offices. While some technology veterans may bash Bumble for offloading their engineering to their parent company, she is unapologetic about the benefits and practicality of the arrangement.

“Had I gone out and tried to do this on my own with no tech support, Bumble would be a year-and-a-half behind. Think of all the marriages and babies and connections we’ve made [in that time],” explained Wolfe Herd.

She continued: “It’s like building a road. If you can get the materials from someone quicker that will make people’s lives easier, why would you say, ‘No, I want to build this with my own two hands,’ just to be able to say I did?”

I asked Wolfe Herd if there are ever times when their team has wished that their developers were sitting in the next room, standing by for a product consultation or roadmapping session.

But Wolfe Herd actually attributes much of Bumble’s success to working in an environment devoid of a dev team. Specifically, she explained that it gave her team the creative freedom to allow Bumble’s message and brand to drive the product, and not vice versa. By letting branding take the front seat instead of product, Bumble leapfrogged the “connections app” phase and became a lifestyle brand.

“How do you have different touch points in a user’s life? How do you reach them on their drive home from work? How do you talk to them on social media? How do you make them feel special? How do you add your brand into their different touch points?” Wolfe Herd says. Her original vision was to build a social network rooted in positivity and affirmations, but asking (and answering) these questions has allowed her to help in building a whole world for Bumble users rooted in positivity and affirmations.

Versace, Balenciaga, Bumble

Last summer if you happened to be walking through New York’s trendy Soho neighborhood you may have noticed a new tenant sandwiched between Versace and Balenciaga on Mercer Street.

In a first for a dating app and pretty much any social app, Bumble opened a physical space as an attempt to formalize the community that was naturally forming around it. At the time she told me that the opening coincided with Bumble’s brand becoming something that people are now proud to associate with in real life.

Bumble’s New York City Hive

This message was repeatedly echoed to me by others around Wolfe Herd, and it seems to be one of the internal barometers the company uses to track its success. Samantha Fulgham, Bumble’s second employee who now leads campus marketing and outreach, explained how male college students are now applying to become ambassadors, interns and even full-time employees.

“We tried to [have male students be campus ambassadors] in the U.S. probably two years ago. They didn’t really want to do it, because they thought it was a girl thing. Now we’re trying it again in Canada and we’ve already had so many guys asking how they can work for Bumble… saying, ‘I want to be a part of this company.’”

And it’s not just college students champing at the bit to associate themselves with the brand. When Bumble launched its business networking product last fall, the startup’s NY launch party was attended by Priyanka Chopra, Kate Hudson and Karlie Kloss, while the L.A. event hosted Gwyneth Paltrow, Jennifer Garner and Kim Kardashian West.

Bumble Bizz’s NYC Launch Party. From L-R: Whitney Wolfe Herd, Priyanka Chopra, Karlie Kloss, Fergie and Kate Hudson. By Neil Rasmus/BFA.com.

A digital response to a real problem

Bumble has been able to grow into the company it is today because it was founded on the basic principle of taking a stance on a contested issue: Women were never supposed to make the first move. But Bumble didn’t stop there, and under Wolfe Herd the startup has been very vocal about making sure they are using their voice to address issues that other companies are taught to avoid taking a stance on.

In the wake of the Stoneman Douglas school shooting, Bumble did something that breaks just about every rule taught in marketing and PR 101: The dating app very publicly decided to insert itself right in the middle of our nation’s ongoing gun debate by banning images of guns on its platform.

“We just want to create a community where people feel at ease, where they do not feel threatened, and we just don’t see guns fitting into that equation,” Wolfe Herd told The New York Times after the ban.

She told me at the time that the move shouldn’t be seen as Bumble taking a hard stance against guns or gun owners, but rather taking a hard stance against normalizing violence on their platform.

While an outsider may have been surprised to see such a fast-growing company break the status quo and decide to take a stance on a political issue, those who know Wolfe Herd will say that doing things like this is exactly why Bumble has become so successful in such a short amount of time.

What’s next?

For an industry that’s been around since the beginning of time, matchmaking sure is having its moment. And even the big players want a piece of the action; Facebook has announced it’s expanding into the dating space. So how does Bumble, a barely four-year-old, non-venture-backed company take advantage of all this attention while simultaneously defending itself from the threat of big players entering the space?

Over the summer we reported that Tinder’s parent company Match was set on acquiring Bumble, first at a $450 million valuation, then a few months later at “well over” $1 billion. It would have been an ironic ending for a company that was at least partially founded because of Wolfe Herd’s negative experiences surrounding her time at Tinder and Match.

Ultimately negotiations fell through between the two companies, and from there things escalated quickly. In March, Match sued Bumble for “patent infringement and misuse of intellectual property,” and a few weeks later Bumble sued Match for fraudulently obtaining trade secrets during the acquisition process. Both lawsuits are still making their way through the courts, but it’s safe to say that a deal between the two is off the table for the foreseeable future.

So what’s next for Bumble? The company is profitable and self-sustaining, and has no need to take on capital or sell itself. But Wolfe Herd acknowledged that the right acquirer may allow them to fulfill their goal of “recalibrating gender norms and empowering people to connect globally” at a much faster pace.

Wolfe Herd explained: “If the right opportunity presents itself, we’ll absolutely explore that and we’ll absolutely always explore the best way to take what we’re trying to do and what our mission is and what our values are. If we can be acquired, that will help us scale 10 times faster and that’s something that’s interesting to us, right?”

But she was also clear that cash isn’t what they’re looking for. “We would only ever consider an acquisition of sorts that brings strategic intellectual capital to the table, strategic knowledge of new markets that we have not yet gone into, and added value in ways that supersedes just straight cash,” said Wolfe Herd.

To the casual observer it sounds a lot like Facebook and its 2+ billion active users could do a pretty good job helping Bumble quickly spread its message around the world.

And Bumble seems to agree. After Facebook’s announcement about its dating play, Bumble issued a statement saying, “We were thrilled when we saw today’s news. Our executive team has already reached out to Facebook to explore ways to collaborate. Perhaps Bumble and Facebook can join forces to make the connecting space even more safe and empowering.”

In a conversation with me following the announcement, Wolfe Herd said that Facebook’s expansion into dating “is actually super exciting for the industry, because if you look at the history of Facebook when it comes to building their own products versus acquiring, they oftentimes attempt to build their own. If those products don’t successfully come to market, there’s usually a transition into acquisition. Who knows what will happen?”

So if Facebook comes knocking, don’t be surprised if Bumble answers… and quickly. But if they don’t, then current indicators are that Bumble will be just fine.

In just four years the company has flipped the switch on app-based dating, taking something that was once taboo and making it something that users are proud to associate with. So luckily for the more than 30 million women (and men) who have used Bumble to break gender stereotypes and make over 2 billion matches on their own terms, Whitney Wolfe Herd didn’t care what she or her company were supposed to do.

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2IdbuiE

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment